Joop Jongeneel May 29, 1943, The Hague

It was two thousand and forty-two steps from the parental home on Weissenbruchstraat in The Hague to the station on the other side of the Malieveld. “Without those two suitcases, it would have been fewer,” Joop thought to himself. “I estimate that I would have come in at just over twenty-six hundred.” He counted everything: the steps of every staircase he climbed, the number of steps to a particular spot, how many cigarettes he smoked per day, how many apples fit in a kilogram. Joop didn’t think of this as a deviation; it happened automatically. In his two small brown suitcases were four trousers, four sweaters, six shirts, four dress shirts, eight pairs of socks, eight underwear, his winter coat, a woolen tie, an extra pair of shoes, his shaving gear, his toothbrush, toothpaste, two washcloths, three towels, a white iron mug, and six packs of cigarettes, his employment contract from Ruys with a letter from his boss, his ID card, and stationery plus a pen to write letters home. On the way to the station, walking along Bezuidenhoutseweg, the beginning of the war already seemed a long time ago. The traces of the battles three years ago had disappeared, and The Hague had taken on the appearance of the stately capital again in these sunny May days. But it didn’t feel the same as before, and that was not only because of the Germans. Last year, father had died of a stomach bleed. Joop got a job at Ruys trading association in the accounting department.

Joop was the third son of the four his parents had. Tom was the oldest, eight years older than Joop. Four years after Tom, Jaap was born, four years after him, Joop, and then, four years later, his little brother Adrie, who was now almost 19. When Joop was about ten, they moved from Alphen aan den Rijn to The Hague, where father started a taxi company with three taxis, three shiny black Mercedes-Benz cars. He hired two drivers. Business went well, and every year they went on vacation abroad with one of the cars. To the Ardennes or to Germany. When brother Tom was 22, in 1934, he met a German girl on one such vacation in Germany. They wrote to each other often, and Tom, who now had a driver’s license, occasionally borrowed the car to visit his girlfriend. A year later, they got married and settled in The Hague. Joop’s four years older brother Jaap played football at VUC in The Hague. He was a star player there and was nominated by chairman Karel Lotsy in 1939 to play in the Dutch national team. Lotsy had good contacts in the world football organization FIFA, and it seemed like a wonderful football career for Jaap, but he never got further than one match against Belgium. After the German invasion on May 5, 1940, Jaap was not asked again. Lotsy, in the meantime, proclaimed everywhere that he had received a badge from Adolf Hitler in 1936. Lotsy became the chairman of the Dutch football association (KNVB), and he reported to the new Ministry of Education that he had no problem with the ban on Jewish referees.

The war also changed the attitude of their neighbors and acquaintances towards the Jongeneel family, especially towards Tom and his German wife. Initially, it was only half-questioning remarks, but after two years, from 1942, the comments became meaner, not only towards Tom and his wife but towards the entire family. In 1942, father died of a stomach bleed, and that was the reason for Tom to decide to leave the Netherlands and live in Germany with his wife. He no longer wanted to endure the constant taunts directed at him and his wife. The big question was how to continue with the taxi company now that father was dead, and Tom was leaving for Germany. Joop didn’t have a driver’s license, and his younger brother Adrie didn’t either. So, brother Jaap had to provide for the income. He was not angry at Jaap for not taking him to the station. Work came first. That morning, he had said goodbye to his mother and to Adrie at home.

Actually, Joop didn’t need to go to Germany. Men who were doing useful work in the eyes of the Germans were allowed to stay in the Netherlands. The decision was quickly made within the family circle. They all agreed, and Joop hadn’t doubted it for a moment: he was going to Germany for the “Arbeitseinsatz,” forced labor. “Do I have a choice?” It had been more of an observation than a question. Adrie could also be called up for forced labor in Germany at any moment. So, the discussion was short: Jaap had been called up, but he had to drive the taxi, so Joop would do labor service in Germany in his place. He had arranged through his boss that he could take Jaap’s place. Although far away, in Chemnitz, it seemed like a reasonable job: Joop would work in the administration of a typewriter factory. His boss had made him understand that they had negotiated for Joop to return to the Netherlands as soon as possible so that he could complete his work for the “Arbeitseinsatz” in Amsterdam. For Jaap, things were different. To make a living from a taxi company, you needed fuel besides trips. The Germans had determined that only companies approved by the Germans were entitled to fuel. Moreover, the taxi rides – mainly taken by German officers – were granted to those taxi companies favored by the Germans. That’s why Jaap became a member of the NSB to keep the taxi business running. He didn’t care if he became unpopular because of it. The death of their father had taken a heavy toll on the family, and especially Jaap harbored a deep resentment against the world. Without saying it aloud, he believed that his fellow countrymen were partly responsible for his father’s death. He had no doubt that the taunting and hateful looks that led to Tom’s departure quickly worsened his father’s stomach ulcer. A stomach bleed had become inevitable. And in father’s case, it was fatal.

Sixty-three men, he quickly saw, had already gathered in the station hall, waiting for the train that would take them to the labor camp in Germany. It was early in the morning, and it promised to be a beautiful May day. Some latecomers arrived with their families. There was kissing and crying, and when the train departed at eight o’clock, all the men hung out of the train window. Some held the hand of their running girl next to the train until the end of the platform. There was waving and waving with handkerchiefs. Joop had sat down. There was room for everyone, but they still had to pick up boys in other cities. So, it could get tight. It wasn’t an ordinary train but a “Sonderzug,” a special train for forced laborers.

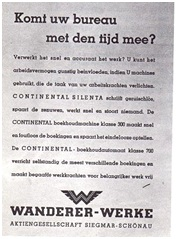

Both in Amersfoort and Deventer, the train made stops to pick up more boys. The train was too small for the large group, and more than half spent the journey sitting and hanging in the aisle. Ultimately, they arrived in Chemnitz the next day. It was already half past two in the afternoon. Through the “Arbeitsamt,” the group went by tram to the Wanderer-Werke factory in Schönau. From there, after some fuss because the factory had just closed, they went by tram again to the wooden barracks in Siegmar, a little further on, where they had to live for the coming period. The next morning, they went together by tram to the factory. Here they received a brief explanation, a booklet of vouchers for food, soap, and such, and a badge with a number. Joop was employee number 9498.

Joop didn’t know anyone in the Lager (camp) with him. In the train, he had met Leo, who also worked at Ruys Handels Vereniging in the Netherlands. Not that they had ever seen each other there, but so far from home, the connection between the two seemed natural. They exchanged stories about their work, and it quickly became apparent that they both had the same supervisors. Leo was in many ways the opposite of Joop: phlegmatic, quick-witted, and a real womanizer.

Soon, they talked about the girls they had seen on the street. The dark-haired, bold foreign girls who had shouted at them in a strange language. Leo concluded they were Russians; or Poles. “Poles are not so dark, they are often blond,” Wim reported, assuming a worldly posture. If the Lager hadn’t been so dismal, they could have imagined themselves on vacation. But Joop absolutely didn’t have a vacation feeling. Concern for home, for mother, and uncertainty about what awaited him here dominated his thoughts. The conversations of Leo and the quickly growing group of Dutchmen around them largely escaped him.

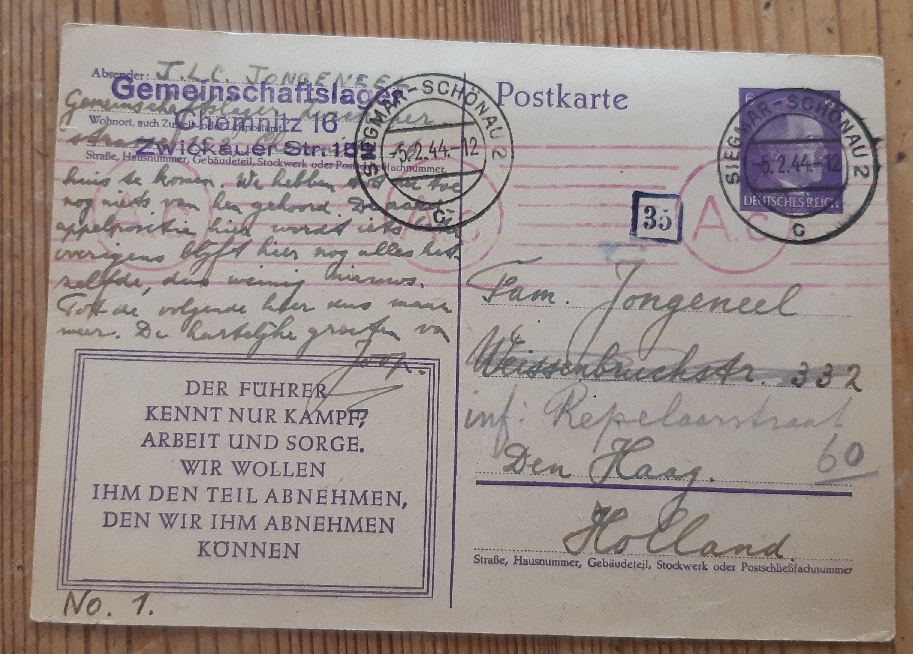

He hoped they would soon be quiet so they could all get some sleep, which seemed difficult enough in the large dormitory. My God, what a mess, he thought, looking around the barracks. I hope I can return to Amsterdam quickly because we can’t endure this for long. Joop was proven wrong. They endured it for a long time and slowly adapted to the harsh life in the Lager. Not that they suffered from hunger or were mistreated. They were just cheap employees of the Wanderer Werke, with a contract and a small salary. Six days of work from early morning until evening. On Sundays, they didn’t work and were even allowed out of the Lager. The food was insufficient and inedible, but it was provided daily, and they even received a small amount of cigarettes. However, constantly living and sleeping in a group and the control over everything they did, including the letters they wrote home, led to dulling and coarsening for all the men.

June 8, 1943, Wanderer-Werke Siegmar-Schönau

Jongeneel Family

Weissenbruchstraat 332, The Hague

Dear everyone,

“It is now quarter to nine, and I just had a sandwich. We had a mandatory roll call this evening. It was only for recruitment for the S.S.; to find out if there were any volunteers for the Eastern Front. There wasn’t much enthusiasm, and we were relieved when it was over. We are still in Lager Siegmar, although a large part moved to the Volkshaus in Schönau last week. Probably, we won’t stay here much longer either. The boys who moved had to be deloused in a steam bath with all their luggage before going to the new Lager. Today, we had to file all day. It’s not easy because you have to stand the whole day, and in the evening, you’re as tired as a dog, and we prefer to get into bed as soon as possible.

You see more foreigners than Germans here: French, Czechs, Italians, Russians, Poles, Norwegians, Danes, Hungarians, Belgians, and Flemings. Loads of Russian girls. Neatly dressed, and some of them look pretty. And groups of Russian prisoners of war with a soldier. We, men of the German race, are not allowed to associate with the Russians and Poles. The girls all have a piece of fabric with the word “Ost” on their clothing.”

Joop wrote to the family in The Hague with iron regularity. Not only because he knew his mother wanted to know how he was doing, but also for himself. This way, he got a diary-like report of his time in Germany, and he would probably want to read it later. And if not him, then his children and grandchildren. Joop liked to plan ahead, and it was no effort for him to think about how his world would look in five or twenty-five years, even here in Germany. “Pete Perfect,” they used to say at school. More like someone who wants to control his life, he had thought of himself. His passion for mathematics, or rather, anything related to numbers, was not strange, and no one was surprised when he started working in the accounting department of Ruys trading association. He hoped that, as a forced laborer here in Chemnitz, he could continue similar work. It had been promised to him, but in the first few days here, he was just one of the foreign laborers, and they all had to do the same work.

During World War II, Wanderer-Werke produced encryption equipment and gyroscopic compasses for the German U-boat fleet. Wanderer Werke also manufactured the legendary Enigma, the encoding machine of the German Wehrmacht used in all important military operations of the Nazis. The Enigma code seemed unbreakable for a long time. The production of Enigma took place in various factories in Eastern Germany, including Olympia Büromachinenwerke in Erfurt and Wanderer-Werke in Chemnitz.

Wanderer Werke was located on Zwickauerstrasse on the edge of the neighborhoods Schönau and Siegmar. It was a broad road running from the center of Chemnitz to Zwickau, about 30 km away. About 2 km beyond the factory was Siegmar station. Nearby was the Lager, and here was also the tram stop from where they went to the factory in the morning. That tram cost Joop 8 marks every week; a waste of money, but if he had to walk every morning, he would undoubtedly be late regularly. Across from the station was the Friseur, the barber where, if you had been at Wanderer Werke for a while, you could have your hair tidied up. Because the barber in the Lager gave everyone the same bowl cut.

They had relative freedom; they could go wherever they wanted on Sundays as long as they stayed in and around Chemnitz. Joop was down-to-earth, but he enjoyed the summer to the fullest and took long walks in the hills around Siegmar on Sundays. They had something irresistibly romantic in this summer.

Probably enhanced by all the new experiences and the constant stress of forced labor, he felt like he was walking in a landscape from which Grieg drew inspiration for Peer Gynt. Here, with the sun on his head and the small half-timbered houses like a kitschy painting around him, life didn’t seem so bad. The walks were also an escape from the constant complaints of his fellow inmates in the Lager. Many people had it much harder at this moment; his mother in The Hague, for example.

Strange that he hardly thought about it anymore, except once a week when he wrote a letter. Because he never forgot that. It was in his new rhythm, as almost everything in his life fit into a self-imposed tight schedule in which new parts quickly became automatic. Joop sat on a hill in a meadow near Rabenstein, overlooking the city of Chemnitz three kilometers away. He quickly sank into pleasant thoughts about the girl he had met at the factory.

She had blond, slightly curly hair, beautiful full breasts, and she had smiled so openly and sweetly at him that he was sure she liked him as much as he liked her. “Ich heisse Christel,” she had said, and he introduced himself in what he thought was the German pronunciation of “Joop.” “Joep” she called him from that moment on, and he left it like that. She lived in Siegmar with her parents, so she wouldn’t be much older than 18. But you didn’t ask a girl about her age. She handed him vouchers for cigarettes and even for sausage, like a girl in elementary school bringing sweets for the boy she liked. Christel, Christel. He repeated the name several times in his thoughts, and involuntarily he whistled the first notes of Suite no. 1 of Peer Gynt. He thought he could learn German from Christel because his German was not something to write home about. Writing home; would he tell his mother that he was in love with a German girl? Better not. She had suffered enough from the fact that his older brother Tom had left the Netherlands because he married a German woman. No, she had enough worries.

Of course, he regularly sent some of the money he earned here. It wasn’t much, but you couldn’t expect much from a wage of 30 marks per week. That’s why Christel’s vouchers came in handy; he could spend less on himself. “I knew you were somewhere around here!” Leo’s voice echoed across the field, and Joop snapped out of his thoughts. “Why are you walking alone? I’ll walk with you.” Leo pretended to be indignant, and Joop stood up to walk towards his friend. “The weather is beautiful,” said Joop, “I can walk for hours through these hills; away from that damn Lager. Do you have cigarettes? Mine are gone.” Leo took out a crumpled pack from his pocket and offered a cigarette.

“Do you know what they give for a cigarette in the Lager? One mark per cigarette already. But yeah, I’m not asking you. As long as mine aren’t finished, you can join in.” They walked down the hill together, and not surprisingly, Leo immediately started talking about women. “Nice girls are walking around here. Yesterday, I talked to that Russian, you know, the one with the black hair. She speaks a bit of German, but you know me, talking is not so important for me. I’ll see her again tonight. Yeah, I’ll make sure they don’t see me with that Russian; I know it’s forbidden to associate with them. But they really want it, Joop. It’s almost too easy. By the way, Christel is also a nice girl. I think I’ll make plans with her next week.” “I don’t think so, Leo. I have my eye on her. You just hold back for once. This one is really for me.” Joop said it with a laugh, but Leo felt that he was serious. “Okay, Joop, you can have her. If you know how to handle it, because you’re not normally quick with women. Or do you want to start something serious with her? Just don’t go to her parents right away, because you might end up having to marry her. You never know how they look at that in other countries. I heard from my Russian that in Uzbekistan, they cut off your head if you get a girl pregnant and don’t marry her. I told her I wasn’t planning on that, and damn, she laughed so understandingly at me that I’m sure I’ll be in bed with her within a week.” “Will it ever be okay with you, Leo? I think you’ll get a venereal disease from all that fooling around with those girls. Actually, we should feel bad, as foreign forced laborers in that damn Germany with bedbugs everywhere on the walls and in our beds, working too hard and having too little food and cigarettes. But I feel fine. The sun is shining, and we’re walking here as if it’s a vacation. So if we also have a nice girl with us, this vacation can’t go wrong.” Leo laughed, and together they ran down the last part of the hill to the road.

Zwickauerstrasse 152

In April 1944, Joop moved with a considerable part of the old group from the barracks to a building located in Schönau, close to the factory: Zwickauerstrasse 152. Their new accommodation was a spacious and large building. The “Volkshaus.” With a kitchen with a cook, a small cinema, and some other amenities. In that respect, they had little to complain about. Only the food was less than meager, causing Joop to trade more than half of the 28 cigarettes everyone could buy per week for 20 pfennigs each with his Lager mates for potatoes.

The distance from the “Volkshaus” to the Wanderer-Werke was 1162 steps, Joop had counted. And from the gate to the entrance of the office, another 38 steps. Exactly 1200 steps in total. So back and forth, it was 2400 steps. 24 was Joop’s special number. His life grouped around that number. He was born on April 24, 1920. 24-04-20, so 2x 24. And even now, it was 24 x 100 steps back and forth.

July 27, 1944, Chemnitz

Joop had been furious all day. He had received a letter from his brother Jaap back home, bringing what he considered alarming news: Jaap wrote that things were going badly. The taxi business was not doing well; the Germans, who occasionally took a taxi, hardly came to him. According to Jaap, the Germans disliked members of the NSB (National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands). Jaap also had a pessimistic view of the war’s progress. He believed that if the Russians on one side and the Americans and British on the other continued, the Germans would face great difficulties. The NSB was increasingly distancing itself from the idea that the Netherlands was part of Germany, and the Germans’ disdain for the NSB was growing daily. Last week, Jaap had signed up for the Landwacht, an organization established by the SS to defend the Netherlands against the Allies. This way, he believed, he would gain respect from the Germans and, consequently, customers. Money had to be earned while it still could. Jaap had asked Adrie to take care of their mother when he had to go out, but Adrie replied that he felt he had already done enough for the Germans during his labor service in Germany.

Joop was especially angry about the fact that Jaap was threatening to plunge his mother and family into misery. What if Jaap were sent to the Eastern Front to fight against the Russians? Who would take care of their mother then? The Germans’ defeat was not clear when it would happen, but for all forced laborers, it was certain that it would happen. And then? A brother as an SS officer! That would be disastrous. They would look down on them, or worse, drive them out of The Hague. In an initial impulse, he thought about telling Jaap the truth in a long letter. But as the day progressed, he realized that all letters were read. Not only by the Germans, but probably also once again in the Netherlands. And then, the dirty laundry would be aired even more. No, be cautious with your opinion. Not too many details. Just about everyday life in Chemnitz. And so, after much thought, he began a letter home in the evening.

Dear Jaap, dear everyone,

Although there has been enough happening lately, I actually don’t know what to write because I prefer to keep my mouth shut about what’s in the newspaper. You never know exactly where to stop, fearing you might say too much. The motto here is: swallow a whole story rather than utter one word too many. Every now and then, you can barely restrain yourself from expressing your opinion to others. But so far, fortunately, that has worked. So, let’s start with something very neutral, namely the Lager.

On Monday, I was quite unwell. I vomited and had a sleep like never before. Maybe it was because I had worked quite a lot the week before: 71 hours. We had an urgent job that had to be finished by Monday. So, it was 10 to 12 hours of work every day, including Sunday morning. I earned my extra bread again. Now, you might think you’d get an appreciative word from the boss, but not a word. And then they say we Dutch are lazy workers. They bring it upon themselves. Those fools (I have another word in mind, but it’s not polite). Then you get thrown in your face today that on our department, “Ausländer” really shouldn’t be there because it’s so secret. They should try it without us! Today we had a good meal again: white cabbage, stew; a whole plate full with three slices of potatoes if you were lucky and two if you were unlucky. Yesterday we had boiled potatoes with “aquarium,” which are herring in formation. Well, let me not write about the food; otherwise, I might get coarse. Now, you might think I’m done complaining, but I have something else on my mind. I get the impression that it would have been better for Adrie if he had stayed a few more months in Germany.

I read the rest of your letter; no comments will be provided, esteemed brother; you can imagine how I feel about it. It’s just a mess, and we all agree on that. We have to figure out how to get through it, but not in the way you’ve come up with; they’ll send you straight to the Eastern Front in an SS uniform. Let’s be glad we’ve made it to the fifth year of the war. Those few months can still be added. It is now Saturday. Yesterday, we had 5 quarters of air raid alarm, and today, almost an hour, but fortunately, nothing happened again. You should be prepared for the fact that the English might be in the Netherlands while we are still here and have no more connection with you. And even if the war ends in three months, it will still be three months before we can go home. I have nothing more to tell, so until next time.

Warm regards from Joop.

A few months later, Joop’s natural optimism had not disappeared, but his sunny view of the current situation had. The work at Wanderer Werke was now more as he expected: he worked in the accounting department where they had something new – punch cards. Cards with holes in them through which a machine could read numbers and calculations from the card. And there were typists who entered the data into those punch cards. Nice girls, but they were not interesting to Joop. Because one of those typists was Christel, and for the past six months, he had been seriously dating her.

So, there was a reason to have a sunny view of this rotten world. But all around them, it became clear that Germany was losing the war. There had been rumors for a long time that after the Germans’ defeat at Stalingrad, the troops were not retreating for tactical reasons as claimed, but that they were genuinely fleeing from the Russians. And they seemed to be coming this way fairly quickly. The English and Americans had landed in France and were advancing towards Berlin. All of this was noticeable to the Germans. They were irritable, and foreign forced laborers were viewed with growing suspicion. In their eyes, every non-German could be a spy and an enemy. So, you had to be extra careful about what you said and did. Joop’s outings with Christel had not suffered yet, but you could tell that people looked at them differently. It might soon be that foreigners would have a curfew. And what about Christel then? Would he only see her at work? And if they had to leave here? There was talk that they would be deployed to another factory. Joop hated it when things were uncertain. And especially when it was because of some madman in Berlin who had to wage war with everyone. And the Russians? Who were they? Of course, the Russian women here were sometimes nice; at least, you didn’t have any trouble with them. But Russian soldiers? Many Germans claimed that they raped women and girls and brutally murdered men. Even Christel became restless from time to time, and she had asked once if she could come to the Netherlands with him when the war was over. But that was nonsense. Her parents lived here, and she had her job. What did she need in the Netherlands? And the Dutch would not react kindly to a

27th of July 1944, Chemnitz

Joop had been angry all day. He had received a letter from home, written by his brother Jaap, with what he considered alarming news: Jaap wrote that things were not going well. The taxi business was struggling; the Germans, who occasionally took taxis, barely came to him. According to Jaap, the Germans had a dislike for members of the NSB (National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands). Jaap also had a pessimistic view of the war’s progress. He believed that if the Russians on one side and the Americans and the British on the other continued as they were, the Germans would face great difficulties. The NSB was distancing itself more and more from the idea that the Netherlands was part of Germany, and the Germans’ contempt for the NSB was growing day by day. Last week, Jaap had signed up for the Landwacht, an organization founded by the SS to defend the Netherlands against the Allies. With this, he would at least gain respect from the Germans and, consequently, customers. Money had to be earned now while it still could. Jaap thought he could manage the Landwacht membership alongside the taxi business because he only had to show up for 24 hours a week. He had asked Adrie to take care of their mother when he was away, but Adrie replied that he felt he had already done enough for the Germans during his labor service in Germany.

Joop was particularly angry about the fact that Jaap was jeopardizing their mother and family with such actions. What if Jaap was sent to the Eastern Front to fight against the Russians? Who would take care of their mother then? When the Germans would lose was unclear; but for all forced laborers, it was a certainty that they were losing. And then what? A brother as an SS member! That would be disastrous. They would be looked down upon, or worse, driven out of The Hague. In an initial impulse, he thought of telling Jaap the harsh truth in a long letter. But throughout the day, he realized that all letters were being read. Not only by the Germans, but probably also once again in the Netherlands. That would expose the dirty laundry even more. No, be careful with your opinion. Not too many details. Just about everyday life in Chemnitz. And so, after much thought, he began writing a letter home in the evening.

Dear Jaap, dear everyone,

Although a lot has happened lately, I don’t really know what to write because I’d rather keep my mouth shut about what’s in the newspaper. You never know exactly where to stop because you might say too much. And the motto here is: swallow a whole story rather than saying one word too many. Every now and then, you can hardly contain yourself from expressing your opinion to others. But so far, thankfully, I’ve managed. So, let’s start with something very neutral, the Lager.

On Monday, I was quite ill. I vomited, and I had such a deep sleep. Maybe that was because I had worked a lot the week before: 71 hours. We had an urgent job that had to be finished on Monday. So, it was 10 to 12 hours of work every day, including Sunday morning. I’ve earned my extra bread again. Now, you might think you would get an appreciative word from the boss, but not a word. And they say we Dutch are such lukewarm workers. They’re asking for it themselves. Those fools (I have another word in mind, but that’s not polite). Then, today they threw at us that “Ausländer” don’t really belong on our department because it’s so secret. Let them try it without us! Today, we had a good meal again: white cabbage, eintopf; a whole bowl with three slices of potatoes if you were lucky and two if you were unlucky. Yesterday, we had pellkartoffeln with an aquarium, meaning herring in the making. Well, let me not write about the food; otherwise, I might get coarse. Now, you might think I’m slowly getting tired of complaining, but I have something else on my mind. I get the impression that it would have been better for Adrie if he had stayed a few more months in Germany.

I read the rest of your letter; no comments will be provided, esteemed brother; you can imagine what I think about it. It’s just a mess, we all agree on that. We have to figure out how to get through it, but not in the way you’ve come up with; they send you to the Eastern Front in an SS uniform. Let’s be glad we made it to the fifth year of the war. Those few months can still be added. It’s now Saturday. Yesterday, we had an air raid alarm for 5 quarters, and today almost an hour, but fortunately, nothing happened again. You have to consider that the English might be in the Netherlands while we are still here and have no connection with you. And even if the war ends in three months, it will still take three months before we can go home. I have nothing more to say, so until next time.

Best regards from Joop.

A few months later, Joop’s natural optimism hadn’t disappeared, but his sunny view of the current situation had. Work at the Wanderer Werke was now more like what he had expected: he worked in the accounting department where they had something new – punch cards. Cards with holes through which a machine could read numbers and calculations from the card. There were typists who entered data into those punch cards. Nice girls, but they weren’t interesting to Joop. Because one of those typists was Christel, and for the past six months, he had been seriously dating her.

So, there was a reason to keep a sunny outlook on this rotten world. But all around them, it became clear that Germany was losing the war. There had been rumors for a long time that after the Germans’ defeat in Stalingrad, the troops didn’t retreat for tactical reasons, as claimed, but that they were really fleeing from the Russians. And they seemed to be coming this way fairly quickly. The English and Americans had landed in France and were advancing toward Berlin. All of this was noticeable to the Germans. They were irritable, and foreign forced laborers were viewed with growing suspicion. In their eyes, every non-German could be a spy and an enemy. So, you had to be extra careful about what you said and did. Joop’s outings with Christel hadn’t suffered yet, but you could tell that people were looking at them differently. It might just be that foreigners would soon get a curfew. And what about Christel? Would he only see her at work then? And if they had to leave here? There was talk of them being assigned to another factory. Joop disliked it when things were uncertain. Especially when it was because some lunatic in Berlin had to wage war with everyone. And the Russians? What kind of people were they? Of course, the Russian women here were sometimes nice; at least, you didn’t have trouble with them. But Russian soldiers? Many Germans claimed that they raped women and girls and gruesomely murdered men. Even Christel got uneasy about it from time to time, and she had asked once if she could come to the Netherlands with him after the war. But that was, of course, nonsense. Her parents lived here, and she had her job here. What did she need in the Netherlands? And the Dutch wouldn’t react so kindly to a German girl now. No, it would be very unpleasant for her. And that’s what Joop had told her as well.

Tuesday, February 13, 1945.

Winter in Chemnitz. Van den Berg and Joop.

There was a thin layer of snow, and it was lightly freezing. A bit south of Chemnitz, in the Ore Mountains, there was almost half a meter of snow in some places, and the temperature could drop well below freezing at night. According to Christel, it wasn’t as cold here in the not-so-high Chemnitz, but for Joop, it was still too cold. The cold winters lasted from November to March, he had learned. Joop wished winter would end soon. Joop had been invited to have dinner at Christel’s home in Siegmar after work. Technically, they weren’t allowed to leave the camp during weekdays, but the Germans had other concerns and were not enforcing the rules strictly. Usually, they had a warm meal in the afternoon and Abendbrot in the evening: bread and usually some soup. But today was an exception. Christel’s uncle, Uncle Friedrich, or Fried as he was called, had shot a deer. Uncle Friedrich was a brother of Christel’s father, Georg Haustein, and had a butcher shop in Thum, a town just south of Chemnitz, in the Ore Mountains. The whole Haustein family lived in the Ore Mountains. Only Georg had moved to Siegmar with his wife Hilde. Despite most of the deer being distributed to Fried’s regular customers, Christel’s family still got a sizable piece, about one and a half kilograms. Joop was enjoying meat again after a long time. It was a feast, and with local wine, the atmosphere in the Haustein household became almost festive. Father and mother Haustein liked Joop, and the discussion quickly turned to why Joop didn’t stay in Chemnitz with Christel. But he had to return to Holland because he couldn’t leave his mother alone any longer. Someone had to take care of the income now, as his younger brother Adrie was too young and unwilling. And it was unlikely that his brother Jaap could keep the taxi company running after the war. He was, after all, a member of the NSB and now wanted to join the SS. The Haustein family didn’t quite understand the latter, but they appreciated that Joop wanted to take care of his mother. Would he come back quickly for Christel then? “Of course,” Joop lied, as he had no intention of marrying a German woman like his brother Tom, no matter how much he loved Christel. He would see later when he returned to The Hague. Maybe after a while, he decided to go back to Chemnitz, to Christel, but he would see about that later. The times were too uncertain to look too far into the future. Joop liked certainties, and a future with Christel had too many unanswered questions. Another bottle of wine was opened, and Joop almost felt at home.

It was around ten o’clock, and Christel wanted to go to bed. There was work the next day. Through the closed windows, the air raid siren of Chemnitz sounded. Father Haustein turned on the radio. The “Luftschutz” Leipzig reported that English bombers were flying south, possibly towards Chemnitz. “Shouldn’t we go to the air raid shelter?” Hilde asked anxiously. “Oh, come on,” replied Georg. “Here in Siegmar, we’re at a safe distance from the center of Chemnitz and far enough from the Wandererwerke. I don’t think bombs will fall here. But I’ll take a look.” Georg Haustein walked outside, and Joop followed him. But despite the almost clear sky, there was nothing to see, except for the swaying searchlight beams of the anti-aircraft guns. Christel, who hadn’t gone to bed yet, stood next to Joop and clung to his arm. Later, the eastern sky lit up in the distance in an incessant flood of flashes. “That’s Dresden. They’re bombing Dresden!” Father Haustein shouted with horror. They stared at the light of the burning city for a while but eventually went inside when it got too cold. “I’ve made up a bed for you in the ironing room,” Mother Haustein said. Joop gambled that the Germans wouldn’t notice him sleeping here if he was at work on time the next morning. And going out in the evening was dangerous anyway, so he had asked if he could stay at Christel’s house overnight. Christel went to bed, and Joop was poured another glass of schnapps by Father Haustein. Georg wanted to talk; he clearly needed to express his emotions. “Dresden is such a beautiful city,” Georg began. “There’s no economic or military target there. Bombing Dresden is shameful barbarism. And the city is full of refugees from Berlin, Leipzig, Halle, Cottbus, Jena, and so on. Everyone thought they were safe from the American and English bombs in Dresden. Dresden is art, Florence on the Elbe, not a target for bombers. Dresden should be safe. What kind of beasts bomb a crowded city and simultaneously destroy centuries of high culture?” Georg burst into tears. Sniffling, he poured himself another schnapps. “Would you like another one?” he gestured to Joop. “No, thank you. I think I’ll go to sleep,” Joop replied to the gesture. He realized that Georg needed to talk to him, but Joop couldn’t handle emotions well, especially not crying men. Georg waved him upstairs, and Joop quickly climbed the stairs to the ironing room where Mother Haustein had made a bed with a wonderfully soft, thick down comforter. Oh, how wonderful after all those nights in the camp on bad mattresses full of lice! Joop took off his pants and shirt, wet the washcloth in the bowl of water, and ran it over his face and body. He didn’t want to stain the snow-white sheets and comforter with his sweat.

But despite the comfortable bed, Joop couldn’t fall asleep. It must have been after one o’clock when the air raid siren sounded again, followed shortly by a growing roar. “Just stay in bed,” Georg called. “They’re probably heading to Dresden again.” Joop walked to the window. A second later, three searchlights from Luftschutz Chemnitz intercepted the bombers. The anti-aircraft guns started barking, but the planes were flying too high to hit well. The noise from the fleet of bombers became terrifyingly loud, despite the altitude at which they were flying. Joop estimated hundreds of planes that continued flying eastward. After a while, he heard the soft but penetrating rumble caused by bomb impacts, like a distant but intense thunderstorm. It wasn’t until half-past two in the morning that it stopped, and Joop fell asleep. He had prepared to wake up early because he had to start work at eight-thirty. But he had no trouble waking up. Just after 6 o’clock, the door opened, and he heard the voices of Father and Mother Haustein, followed immediately by the voices of strangers. Joop got dressed and went downstairs. Christel was already up and dressed. In the room stood an unknown family, looking as if they had been sunburned and then walked through a severe sandstorm. Their hair and faces were gray from dust and ash. “Sit down,” Mother Haustein began. “I’ll get clean clothes for you. Georg, give them a cup of coffee, and if they want, something to eat.” The story came out in short, measured chunks: it had been terrible. After the first bombing, they had fled and managed to ride in the car of a musician from Chemnitz who had rehearsed for a performance at the Semperoper in Dresden. The musician had waited for the all-clear in a shelter during the first bombing, then run to his car, which was still intact, taken them along, and driven as fast as he could. They had just been in time because Dresden had been completely obliterated by a giant fire after a second bombing. The woman from Dresden turned out to be a distant relative of Mother Haustein, and when the woman started crying, even Georg couldn’t hold back tears. “You can stay here until you have a house again,” he said in a spontaneous impulse. Joop had become entirely unimportant and invisible, even to Christel. He stayed in the room for a while, then put on his coat, thanked Father and Mother for everything, took Christel by the hand, and together they left for the tram stop. They arrived at the Wandererwerke well in time; he said goodbye to Christel (as kissing really wasn’t allowed here at the factory), punched his card in the time clock, and walked to his office section. In the corridor, he met Leo. “I hear they really got those Krauts good in Dresden last night,” Leo whispered in Joop’s ear. “Get lost, Leo,” Joop snapped, leaving Leo bewildered. “He probably didn’t get to fool around last night,” Leo mumbled to no one in particular.

April 20, 1945.

There was hardly any work left at the Wanderer Works. Last month, Chemnitz had been heavily bombed by the Allies. The city center was mostly destroyed, but the complex of the Wanderer Works had been spared. They could still work, but the Germans were mostly preoccupied with themselves now that the end of the war was so clearly in sight. The Red Army of the Russians had approached to the edge of Chemnitz. According to rumors, they had taken a position in the Zeisig Wald located to the east of Chemnitz. The forced laborers didn’t quite understand why they didn’t advance and conquer all of Chemnitz, but the Russians probably didn’t mind. Winter’s cold had passed, and apparently, they were resting in the sun, awaiting the end of the war. The camp at Zwickauerstrasse 152 was located directly east of the Wanderer Works, whose tall chimney was visible from all of Chemnitz. It was Joop’s birthday – he turned 25 – and he was celebrating with a few compatriots in the canteen when they heard the whistling of shells. Someone looked out the window and saw that the Russians were using the distant chimney of the Wanderer Works as a target from their position.

The third shell took a chunk off the top of the chimney. Suppressed cheers rose from the group of Dutchmen. Then a loud bang; seconds later, the cook came rushing into the canteen in complete panic. Stuttering and stammering, he explained that a shell had flown through the kitchen window and landed in the large pot of soup he had just been stirring. Fortunately, the shell hadn’t exploded, but the cook wasn’t entirely convinced that he had survived. Thunderous laughter brought him back to harsh reality, and cursing, he shuffled to the stairs to go to his room. “Hey, cook! What about our soup? And you were going to bake a cake for Joop’s birthday,” Gerard called after him.

Some beer and schnapps were produced, and during the impromptu birthday party, a conversation unfolded about how long they had to stay here. There was no more work, and it was getting more dangerous by the day. In fact, they were in the front line, although there was no heavy fighting. “I don’t think the Germans will stop us if we leave,” Leo suggested. “We need to wait for the right moment and then leave.” “But how do we get to Holland? Not through the Russians, I think, because that’s too dangerous. And on the other side, there’s fighting against the Allies. We shouldn’t get involved there either.” “If we stay here, we’re also in danger,” Wim interjected into the conversation. “Everyone has to decide for themselves what to do,” Leo replied, “if we all start walking, we’ll be an easy target. So, make a plan and leave, I’d say.” And with that, the discussion in the large group was closed for everyone. Friends gathered in pairs or in threes to discuss. Joop and Leo also had a discussion. “Joop, we’ll go south of Chemnitz towards the west. In the south, there’s no fighting yet. And we’ll walk until we encounter the Americans.” “Sounds good,” Joop said, “but we’ll never be able to take all our stuff. How many suitcases do you have? Two? I have two as well, so that won’t work. I suggest we each take one suitcase with the most essential items and leave the other suitcases at Christel’s place for now.” “Do you think Christel’s parents will be okay with that? And how will we ever get those suitcases back?” “Yes, Christel’s parents will probably be okay with that, Leo. And how we get those suitcases back is the least of my worries right now. I’ll be overjoyed just to make it back to the Netherlands in one piece.” “Well, if you arrange that with Christel as soon as possible, I’ll figure out a route.”

It wasn’t until May 1st that the opportune moment presented itself. They had heard the rumor that Hitler was dead. The Germans were confused and uncertain about whether they should keep fighting or if it was all over now. “So, no more waiting; let’s get out of here,” said Leo. “If those Krauts get scared, they’ll shoot us.” Joop and Leo’s suitcases were delivered to Christel’s home. The farewell from Christel was emotional and intense, and for the first time, Joop dared to kiss Christel while her parents were watching. Joop knew that he would probably never see Christel again. She fit perfectly into the life he had lived here in Chemnitz but not at all into his life in the Netherlands. He had never mentioned Christel in the letters to his family. That part of his diary remained in his head. And maybe that was more truthful than it could ever be on paper. But Christel still hoped he would come back. Especially now that they left their suitcases with her. Joop couldn’t bring himself to tell her straight out that he thought he would never see her again, and that thought made him extra emotional. Under no circumstances could Leo notice. He would continue to tease Joop for the rest of the long journey. So, he tried to make the farewell seem nonchalant: a firm, long kiss, and then waving with a smile as he walked away. But Christel held onto him and burst into tears. Father Haustein turned around and walked inside, while Mother Hilde gently pulled Christel away from Joop and gave him a short kiss on the cheek. “Come back when everything is over,” she said as a farewell. Joop felt a tear roll down his cheek from the corner of his eye and, without saying anything, bent down to their cart with the suitcases. “Walk, Leo, we still have a bit to go, and it’s already midnight.” Leo called out “auf wiedersehen,” and they were off. Leo had arranged a cart somewhere – probably stolen – where their two remaining suitcases could be transported. Because walking all the way to the Netherlands with a suitcase seemed too heavy.

Heading Home.

Joop writes about the journey in his diary:

“May 1, 1945. 12 o’clock: left from Wanderer Works through Neukirchen, Pfaffenhain, Niederdorf, Lugau, Olsnitz, and Hohndorf. 7 o’clock: encountered first Americans. Slept at Hugo Grabner’s in Hohndorf. Wife’s name is Gretl. Son Jörgen is 1 ½ years old.

The second of May also went smoothly according to the brief notes in the diary:

9 o’clock: through Liechtenstein to Glachau. 1 o’clock: arrival at the town hall. Quartered in Aue barracks.”

And here, the journey stalled. They were held by the Americans. Everyone was questioned and checked. On May 6th, the rumor circulated in the barracks that the Germans had surrendered in the Netherlands. Leo and Joop now wanted to get home even faster, but the Americans held them back with hygiene inspections, questions, and promises. On May 9th, a couple of American soldiers approached them with a half-empty bottle of whiskey in hand. “Hey Dutchies. War is over!” They let Joop and Leo take a sip from the whiskey bottle and gave them a pamphlet from S.H.A.E.F., Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force. On one side, the headline was printed in bold letters: “PEACE,” and on the other side, the French headline read: “VIVE LA PAIX.” Underneath was the smaller headline: “Allemagne a capitulé.”

Leo and Joop believed it. For them, the war was, in fact, already over when they heard that the Netherlands was free. And there was no more fighting here; they were with the Americans, and they noticed little difference from the day before. Their biggest concern was how to get home quickly. The next day, they set off early in high spirits, but after an hour and a half of walking, the cart broke down; the axle of the front wheels had snapped. They even asked at a farmhouse if anyone knew how to fix the cart, but in the end, they left the broken thing and walked back to the barracks with their suitcases. It was only towards the end of the afternoon that they arrived there. After everyone had had bread for dinner, they were called to assembly, and they were informed that now that the war was over, everyone would be brought home as soon as possible. A bus had been arranged to Eisenach. The next day, on May 10th, this bus departed around 12 o’clock, and they arrived in Eisenach at 6 o’clock in the evening, where there was no space left. They were directed to Lichtenau, but they could only go there the next day. They were given a place to sleep for that night in the “Vereinshaus.” The next day, they were taken by bus to a camp under American command: Lager Herzog for Displaced Persons.

Joop and Leo expected that they would be home soon now. That didn’t happen. They were held by the Americans for 19 days. Officially, the Americans claimed that they wanted to sift out high-ranking SS officers or other high-ranking Nazis hiding among the groups of refugees. However, the rumor had it that they were primarily searching for German atomic scientists. The war was over, but they were not truly free yet.

Finally, on May 31st, they set off towards the Netherlands with a bus specially arranged for the repatriates in the camp. The driver got lost, so after seemingly endless wanderings, they finally reached Enschede at 4:15 on June 1st.

Back in the Netherlands, almost home, free! That was disappointing. Everyone was transferred to camp Bato. To their horror, they ended up behind barbed wire in a kind of prisoner camp. Some compatriots insulted them as collaborators. The next day, they were drummed out of bed at 5 in the morning, deloused, and medically examined. At 6 o’clock in the evening, they were moved to camp Vronen in Enschede. Only after two days had they convinced the interrogator from the domestic armed forces that they had been forced laborers and not Dutch SS men who had fought on the Eastern Front. They were free to go, but they had to figure out how themselves. With the help of a railway worker, Joop managed to take a freight train to The Hague. Unannounced, he stood there in front of his mother, who burst into tears.

Joop quickly resumed work at Ruys in Amsterdam. A month later, Mr. Buytenhuys, the new boss in Amsterdam, solemnly pinned a ribbon with the likeness of Queen Wilhelmina on him. Joop wasn’t clear about what it was for, and the thing disappeared into a box in his room.

Christel stayed behind in Chemnitz, where daily life for the Germans was exceptionally difficult under Russian occupation. There was hardly any food. She wrote to Joop several times and, first cautiously but increasingly urgently, appealed to Joop to send a package of food. But despite these pleas for help, Joop did not respond. Only after a dramatic letter from Christel, in which she wrote that she weighed only 44 kilograms, did Joop reply. But a real correspondence never developed.

In 1949, Christel married Eberhard Köhler, a young engineer from Chemnitz.

Although Christel had promised Joop to send the suitcase he left with her, along with Leo’s, to the Netherlands as soon as possible, it hadn’t happened yet. Because it wasn’t that easy. The Russians who occupied the eastern part of Germany were harsh and strict. Germans were currently seen as untrustworthy and defeated Nazis. In this time, sending suitcases to the west was a hopeless task. It wasn’t until the spring of 1956 that the situation allowed Christel, with some confidence but still with fear in her heart, to have the suitcases sent by former colleague Genscher from Wanderer Works by parcel post by train to Eindhoven. There, they were delivered by van Gend and Loos to Noordbrabantlaan 92, where Joop lived with his wife Wiesje and two sons.