Wiesje Rubens

‘How dare you show me such a rag! It’s dirty, crumpled, and not well-finished.’ Wiesje looked at the ground. She hated the embroideries she had to make. That fiddling was not for her. ‘You’re just a bit clumsy,’ her mother Toos would say at times. And she also had sweaty hands, making embroidery a torment. It cost blood, sweat, and tears. The nun in front of her looked down on her disdainfully. ‘Go ask our Lord to rid you of that sloppiness and filth.’ Wiesje was dragged by her arm to the cellar of the convent school. She had to kneel and pray until lunchtime. When the bell finally rang for lunch, Wiesje ran home with sore knees. Her father Theo opened the door, and Wiesje burst into tears. Stammering, she told him what had happened. Theo instructed the cook to continue preparing lunch for the guests and jumped on his bike. At school, he demanded to speak to the headmistress. Wiesje didn’t know exactly what was said, but her father came home with the news that she would go to another school. She no longer had to be bullied by those nuns. What did they think? That they could avenge the crucifixion of Jesus on a child of a Jewish father? From that moment on, Wiesje hated Catholics. No, not Catholics because her mother was Catholic, and some of her best friends were too. She hated the church and the hatred that the church spread in the name of the God of love.

Wiesje Rubens was born at 11:45 a.m. on February 19, 1922, at Demer 32 in the center of Eindhoven. On her father’s birthday.

Father Israël Rubens was Jewish and worked in the hospitality industry. Her mother, Toos de Cates, came from a good Catholic family with eleven children. Her father had fallen in love with Toos, but marrying a Jew was really not acceptable in a good Catholic family. To be accepted, he first called himself Isidoor, but that wasn’t Catholic enough. Then it became Theodoor, and that was acceptable. It was shortened to Theo, and that’s what he was called by the whole family. Theo had been in love, and besides, he wanted to get rid of that eternal label ‘Jew.’ He had, as the Amsterdam branch of the family called it, taken a goyishe kalle. Toos’s family had insisted that Theo be baptized Catholic, but he had refused. For Theo, it was all about outward rituals, like putting on a party hat at birthdays. He believed in the goodness of people, in socialism, and not in God. So why should you be registered with the Jewish community or baptized Catholic?

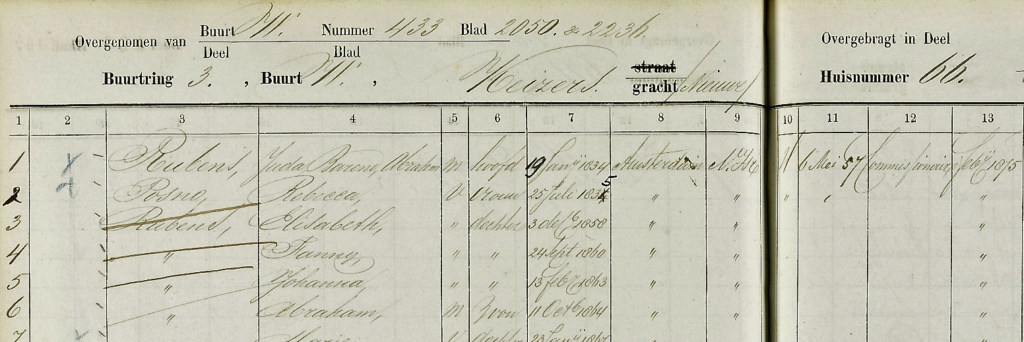

The misjpoge was large, but contacts with most of them, the Amsterdam branch, were limited. Grandfather Abraham Rubens came from a fairly wealthy Jewish mercantile family in Amsterdam, a family of major wool and grain traders. The daughters – what they called – married well. The Rubens clan consisted of several families, including the liberal Jewish Posno family with traceable origins from Poznan, Poland. The Rubens family were Eastern Jews. Ancestor Salomon Ruben married Eva Salomon Hamburger, daughter of David Soezan or Schuschan (1680 – 1742) from Schush or Susa in Iran. But a few years later, he married Clara Knendele, Wiesje’s mother. The Rubens family adhered fairly strictly to the faith. Grandfather Abraham had 10 brothers and sisters. They lived in a beautiful canal house at Nieuwe Keizersgracht 66 in Amsterdam.

Keizersgracht 66

Grandfather Abraham suffered from epilepsy from a young age. He met Grandma Elisabeth van Loen, a Jewish woman from Amsterdam who came from what was called a ‘lesser family.’ But she was Jewish, so the family gave permission for a marriage; under conditions: the family was willing to support him, with the argument of his physical condition, but then he had to renounce any claim to his share of the family fortune. He agreed, and a substantial lifelong allowance was agreed upon for him and his children. Grandfather and grandmother settled in a reasonably nice house in the lower part of Nijmegen: on Stockumstraat, near the Valkhof, dating back to the time of Charlemagne.

Abraham’s children were allowed to come to Amsterdam for a short vacation now and then. When they arrived at Central Station, a chic carriage was waiting for them, owned by the Rubens family. They rode like princes and princesses via Damrak to the mansion on Nieuwe Keizersgracht. Theo felt very special then but was also a bit embarrassed by the exaggerated fuss. Arriving at Keizersgracht, the door was opened by a butler in a nice livery and not, as Theo hoped every time, by his grandmother herself. Grandpa had passed away two years before his birth. Grandma was kind to the children, but Grandpa Abraham was no longer there. From Abraham’s sister, Aunt Fanny, they each received a silver guilder when they left; a fortune at that time, considering that a maid earned three guilders a week. Theo was always quite impressed by their family visits to Amsterdam. On the other hand, he found the ride in the carriage a bit embarrassing, and although grandma probably really loved them, she remained somewhat stiff. Children were not allowed to do much. He had a good time, but he was always glad when he was back home in Nijmegen. Grandpa Abraham died in 1927 of throat cancer, not epilepsy.

Grandpa Abraham’s children all completed their secondary education. Theo went into apprenticeship for a cook in Amsterdam after school. He received a thorough education in very reputable kitchens of hotels and restaurants in Amsterdam, such as the Amstel Hotel and Hotel Polen. After his training, he worked as a waiter there, but a year later, Theo got a job in a café-restaurant in Den Bosch. He commuted for his work to Den Bosch but continued to live with his family in Eindhoven, where his two brothers and sister Lea also lived.

Sometimes Theo proudly told that he was an anarchist in his youth and a member of a group of anarchists: the Nachtkaarsjes, so named because they regularly undertook nocturnal actions. Theo called this anarchist past a bit of boys’ behavior. At the end of the 1920s, he joined the SDAP, the socialists. In Catholic Brabant, this was not appreciated, but at his job, he had not had problems with it until then. His boss was an easy-going Brabander who prided himself on getting along well with the ‘common people.’ He was, as he said himself, ‘a man of the people’ and had always had to work hard to achieve what he had achieved. In the restaurant, mainly people from the better circles of Den Bosch came. In the café area, it was a lively crowd of workers who came for a pint or more after work. And on Sundays, whole families came to the café for a drink and a sausage roll after church, and after half an hour, the men stayed for another pint and a chat with other men, while the women with children went home. At Easter, his boss asked for the ‘Easter notes’ from people: as good Roman Catholics, you had to observe Easter, i.e., go to confession and attend Easter Mass. If you did that, you could ask the priest for a note that you could show to your employer. Father priest had enough influence to force employers to ensure that only good Catholics stayed at work. That you were a good Catholic had to be proven, among other things, by your Easter note. But, of course, Theo couldn’t show an Easter note – he didn’t go to church. Whether it played a role that he was also a socialist and a Jew was not clear, but he was fired on the spot. He moved with his family – he had a son Barend and two daughters, Beppie and Wiesje – to the also Catholic Nijmegen. Here, Father priest was not the most important man in the city, and Easter notes were not requested. Moreover, Jews lived almost problem-free among non-Jews there.

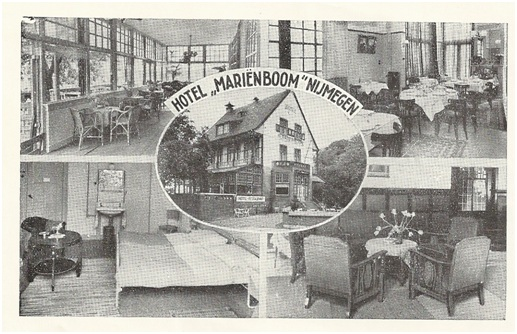

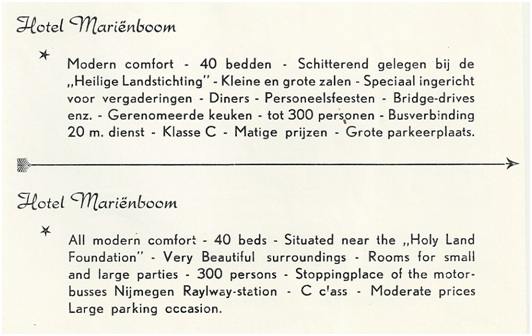

Around the same time, Father Theo and his brothers and sister received an offer from the family in Amsterdam: the family could continue with the allowances to the children of Grandfather Abraham, or they could receive a considerable amount at once, after which the allowances would stop. In their youthful recklessness, they opted for the amount at once. Theo had never told how much it was, but enough to be able to buy hotel Mariënboom in Nijmegen immediately and pay in cash. Theo did not like obligations to capitalist institutions like the bank. He also always wanted to remain completely independent. And so, Theo became the proud owner of hotel Mariënboom on Groesbeekseweg, opposite Mariënbos. It owed its name to an ancient lime tree. In the city annals of 1538, we already read about a chapel called Mariënboemcken and about the estate Mariënboom. And when the hotel was built around 1900, it was, of course, called Mariënboom. Mariënboom was a stately hotel and an entertainment center on the beautiful outskirts of Nijmegen, attracting well-to-do people from home and abroad. The hotel also served as a meeting place for people from the region. As a special attraction, the hotel had raccoons that repeatedly escaped into the Mariënbos. Upstairs, there were spacious guest rooms, furnished according to the nature of that time. In addition to a restaurant, there were beautiful halls for receptions and parties. In the summer, the people of Nijmegen could come to enjoy their drink or coffee outside. There were tennis courts, and children could have fun in a large playground behind the hotel. There was also a stable, managed by others. But you could ride a horse through the Mariënbos. For the children, there was a track in the playground where you could ride ponies. At the edge of the property was a small zoo. And, of course, there was a large hotel kitchen and a wine cellar. Wiesje was thirteen years old at that time. And because the age between thirteen and twenty is so immensely transformative in a person’s life, she felt like she had always lived in Mariënboom.

Wiesje grew into an attractive girl, wanted by many young men. But her loves turned out less well. The Netherlands was changing. In Germany, Hitler had seized power, and Kristallnacht made clear what his intentions were. In the Netherlands, the NSB propagated fascism and anti-Semitism. At a very young age, Wiesje had a relationship with Albert Evers of the Royal Military Academy in Breda. A relationship that almost led to marriage. The relationship was (beginning of 1940?) broken off because Wiesje was seen kissing another boy (Ab’s diary). Wiesje didn’t mourn for a long time. Plenty of boys. And the threat of war was considerably less interesting than love or the desire for it.”