May 10, 1940

On May 10, 1940, the Germans invaded the Netherlands. Armed with submachine guns, they rode motorcycles along the Groesbeekseweg. There was gunfire, and Dutch soldiers lay dead here and there. Chaos reigned in Mariënboom. Guests from The Hague tried to get home, but as they reached the Waal Bridge, it was blown up by Dutch soldiers, along with some German tanks and trucks. Theo ordered the staff to dig a pit that could serve as a shelter. After a few days, it was over. The Netherlands capitulated, and everything seemed to return to normal. The Mariënbosch monastery, located in the Mariënbos, was requisitioned as a hospital for German soldiers. German soldiers, somewhat recovered, often sat on the terrace, in the café, and in the dining room of Mariënboom, eating or drinking beer. Wiesje paid little attention to the advances of the young German soldiers who begged for the attention of the attractive blonde young lady. The Germans were served like any other guests: politely but distantly. One of the Dutchmen who frequented Mariënboom was Louis, a handsome, quiet guy from The Hague, living in Nijmegen. Wiesje fell for his advances. She fell deeply in love with him, and he came to Mariënboom almost daily. They even started making tentative plans to get married.

It was a Monday afternoon when one of Louis’ friends suddenly stood at the buffet where Wiesje was pouring drinks for a few officers. He was pale and awkwardly asked if Wiesje could spare some time. “What’s going on?” asked Wiesje, feeling a strong sense of panic. “Louis was waiting for the train on the platform. It was very crowded, and when the train entered the station, everyone pushed forward. Louis fell and got under the train.” Wiesje covered her mouth with her hands and remained silent for a while. Then she screamed, “What happened to him? Tell me!” “He was killed instantly,” the friend replied almost inaudibly. At that moment, Theo arrived and heard the last sentence. “Louis?” he asked curtly. “Yes,” stammered the friend. Father Theo wrapped his arms around Wiesje and held her tightly without saying a word. They stood like that for more than a minute, while someone from a table shouted, “Wo bleibt mein Bier?” Wiesje suddenly pulled away and rushed to her room. It took half a year before Wiesje paid attention to boys again.

Clubs and associations were forbidden in occupied Netherlands, but sports clubs were still allowed. Walking clubs were formed everywhere. One of those clubs was the Catholic walking club NIMWA, and the young men from that club always came to Mariënboom, mainly because Wiesje and her sister Beppie were there. Wiesje received noticeable attention from one of them, Jo Thuis. Jo was very Catholic. One of his brothers was a priest, and his sister was a nun. According to Wiesje’s family, he was an enormous bore, but Wiesje was attracted to him. They started dating, and for at least a year, Jo came to Mariënboom daily. He was concerned about the danger Wiesje faced as the daughter of a Jew. It was better to be Catholic, he thought. The Germans would leave you alone then. And Father Theo had to be especially careful. One day, Jo’s priest brother came with him, and they had a long conversation with Theo and Toos. The idea of having Theo and Toos married in the Catholic Church emerged. Theo agreed. “It can’t hurt,” was his skeptical response. And so it happened that Theo and Toos remarried in the Catholic Doddendaalkerk with Pastor Frankenmolen. In a back room, as Theo was not baptized as Catholic and did not want to be, so it couldn’t happen in the church itself.

Forbidden for Jews

As on all public places, the sign “Forbidden for Jews” hung almost from the beginning of the war at Mariënboom. Theo couldn’t enter his own hotel; at least not in the publicly accessible part. But because he was an excellent chef, he continued to prepare meals at the request of the Germans. In early 1943, most of the remaining Jews in the Netherlands, as well as in other countries, were arrested and transported to extermination camps. The Germans had perfected their methods of extermination, allowing them to send large masses of Jews to the camps for what Hitler called the “Endlösung”: the total destruction of the Jewish race. Theo had escaped for the time being because he enjoyed a kind of protection from the German officers who greatly appreciated his cooking skills. They could somewhat justify this because Jews married to non-Jewish women were scheduled for transport later than Jews with an entirely Jewish family. It wasn’t all clear yet, but in the rigid order that the Germans had planned, half-Jews and children from a marriage between a Jew and a non-Jew were later on the list for transport. Ultimately, everyone with Jewish blood had to be destroyed because the Endlösung was inevitable.

Van Dijk was the police commissioner in Nijmegen, an NSB member, and a fervent Jew-hater. He never came to the “Jew hotel” Mariënboom. He knew Theo well. When they were kids, he lived on the same street as Theo. And his mother had been good friends with Theo’s mother. Van Dijk found it unimaginable that he had once been friendly with Jews. And to make it clear to Theo that “subhumans” like him were only good for serving and crawling before the Aryan race, he decided that Mariënboom would become a holiday home for the wives and children of NSB members and Dutch SS members. Every two weeks, new groups came for vacation in Nijmegen and its surroundings. Once, a large group of NSB members with their families from The Hague came. It was the lowest scum imaginable. A son of one of the NSB members wandered through the hotel and entered the kitchen, where he saw Theo. “My father gives me a dagger, and I’ll stab all the Jews with it.” Theo replied, “Do you know what Jews are?” No, he didn’t. “Well,” said Theo, “you always walk barefoot in the grass. And in the grass, there are all these little Jews that bite into your toes.” Screaming, the child ran back to the terrace where his parents were sitting, “The Jews want to catch me.” The next day, Theo had to go to Commissioner van Dijk. “First of all: you were seen on the street without a Jewish star,” lied van Dijk, “For that, you can be sent to a camp without mercy.” Theo remained outwardly calm, but internally he trembled with anger and fear: it was over, he was going to be transported. “If your mother saw me standing here like this, you would get a beating.” Theo bravely said, “Even my mother would understand that a solution must be found for the problems that Jews have caused for centuries. But you’re lucky that I’m the commissioner here because someone else would have already sent you to a labor camp.” He continued, “You understand, of course, that I can no longer expose people to the company of Jews. And the Germans may protect you, but it’s over with this unacceptable mixing of our people with characters like you. Therefore, from now on, your hotel is closed to the public. We’ll put up a sign today.” Theo felt a weight lift from his heart because he wasn’t being deported, but once outside, he didn’t know if this was an outcome to be happy about.

Back at the hotel, Theo told the German officers that they were no longer allowed to come because of van Dijk — he deliberately mentioned the name. “Does that boor think he can decide that for us?” one of the officers replied. A week later, a new German regulation came: Mariënboom Hotel would now be the accommodation for German officers from the hospital. Van Dijk’s response came quickly: “Then the Jew with his family must leave.” The Germans reluctantly accepted the authority of the commissioner. They requisitioned an upstairs apartment in the Stieltjesstraat where the Rubens family could live. Provided that Theo still came to Mariënboom to cook on important occasions. And so, they had been living in the spacious upstairs apartment for a year. Van Dijk was shot dead some time later, reportedly by the resistance.

Moving to Stieltjesstraat was a temporary evil for Wiesje, like the whole war was a temporary tough period that one had to get through without paying too much attention to the German occupiers or Dutch traitors. She could also understand that the family in Amsterdam had not followed the advice to leave for America or Switzerland, although they could easily afford it. But last year, the news came from Amsterdam that they all — the Rubens family and the related Posno and van Loen families — had been deported to Westerbork. And rumors had it that they had been taken from there to concentration camps in the East: Auschwitz, Treblinka, or whatever those places were called. Father talked little about it. Sometimes he told Mother that he was afraid of never seeing them again, and then tears welled up in his eyes. Wiesje didn’t understand those tears because Grandfather Abraham and his children had actually been disowned by the family in Amsterdam. And only because Grandfather Abraham had epilepsy. Wiesje had heard that the Amsterdam family considered it a disgrace that Father Theo had married a non-Jewish girl and didn’t raise his children with the Jewish rites, customs, and the Hebrew language — a family cast out before the war because Grandfather got married and the Amsterdam family made difficulties about his illness and money. They were practically not worth a tear. Would they have ever shed a tear for them or for Grandfather, who had epilepsy? Wiesje’s judgment of the Amsterdam family was harsh, but the idea that her family had been deported by the Germans filled her with an unexpected Jewish determination — a feeling of Jewish solidarity that she had never felt before.

Nijmegen, February 22, 1944.

It wasn’t an extensive lunch, but Theo, Wiesje Rubens’ father, was a good cook and always managed to make a good meal despite the scarcity. Wiesje worked at the Dobbelman soap factory in Nijmegen and received a few pieces of soap weekly to take home. These would then be exchanged for sugar, butter, potatoes, or occasionally even real coffee. And from the kitchen of the Dobbelman canteen, Wiesje always received her lunch in a tin she specifically brought for this purpose.

Just before twelve o’clock, the air raid siren had sounded, and shortly afterward, they heard the monotonous drone of high-flying bombers. The Rubens family had stayed at the table because Allied bombers often flew over Nijmegen on their way to German cities where bombs were dropped. Around one o’clock, the “all clear” signal sounded, and Wiesje immediately got up from the table. She absolutely did not want to be late for work. It was only a ten-minute walk to the Dobbelman soap factory in Graafsedwarsstraat in Nijmegen. From their upstairs apartment in Stieltjesstraat, across the station square, a hundred meters through Arend Noorduijnstraat, crossing Graafseweg, and she would already be in Graafsedwarsstraat. She quickly put on her coat, shouted as she left the door, “See you tonight, Mom and Dad!” and started running. Her father’s words briefly crossed her mind: “Girls run, women walk.” Wiesje was 21 and already felt like a woman, but the desire to be on time won over her father’s words. Wiesje hadn’t reached the factory gate when she heard the sound of planes again, now louder. She wasn’t worried about it. The sirens had given the “all clear” signal, so these were probably German planes. Suddenly, there was a dull and deafening boom. She looked around in shock and saw flames and clouds of debris and smoke. Anxiously but not in panic, she ran into the factory, where her colleagues crowded around the windows.

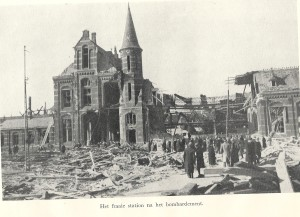

“Away from those windows!” shouted the boss. “To the air raid shelter.” And quickly and obediently, the entire staff, mostly women, walked towards the shelter in the corner of the factory hall. After a few minutes, it was silent; dead silent. Everyone stayed in the shelter for a while, but two minutes later, when it remained quiet, a few Dobbelman employees, including Wiesje, ventured outside to see what had happened. Large black clouds of smoke rose from the nearby city center. Wiesje walked back into the factory, put on her coat, and walked to Graafseweg. With horror, she saw in the distance that the station had been hit. She rushed there but was stopped before the station square by two policemen. Over their shoulder, she saw that the square was littered with dead and wounded. Her first thought was: Nellie, her colleague, always walks across the station square to Dobbelman. And she never walks fast. For her, a burning tram. The station itself was also hit, and a destroyed train still stood at the platform. She looked at the gruesome scene as if paralyzed. Smoke and destroyed houses were also to the right of her, towards the city center.

A panic struck her heart: “Mom and Dad! Is Stieltjesstraat hit?” She squeezed past the policemen who couldn’t stop her and ran – along the edge of the station square to avoid seeing the dead – home. The beginning of Stieltjesstraat was damaged, but further where their house stood, everything was still intact. She ran up the stairs and shouted as she ran, “Dad, Mom!” Immediately, she heard her mother’s sobbing scream as she came down and threw herself around Wiesje’s neck. “Child, child, I was so worried; Dad said you always ran fast and would already be at Dobbelman, but I was in mortal fear.” Father Theo also came downstairs. And again, Wiesje saw a tear welling up in the corner of his eye. “Good thing you’re not yet a lady,” and a smile appeared on Wiesje’s tear-streaked face. Wiesje didn’t go to Dobbelman that day.

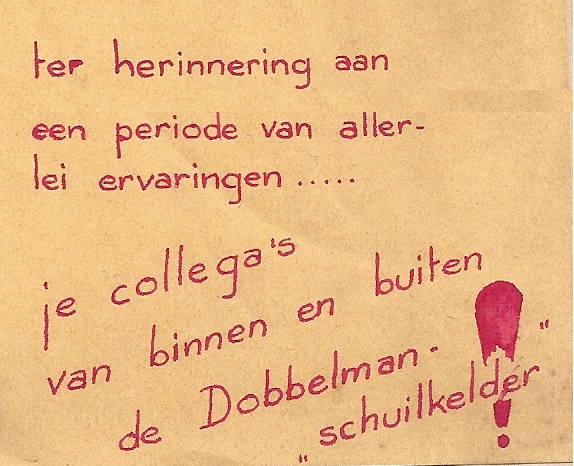

The next day, she heard at the factory that it was an American bombing. “A mistake,” was Wiesje’s openly expressed suspicion. The city center was largely destroyed, and there were at least five hundred dead, but that would probably be much more because many were still seriously injured in the hospital, and who knows who else would be found under the rubble. Seven colleagues were missing from the factory. They already knew that three of them were dead, including Nellie, who was hit on the station square with two friends. And a friend of Wiesje’s brother Barend, Ans, who lived at number 6 in Stieltjesstraat, had a bomb fragment in her head and died instantly. There was a question: if there were still girls who could help at the emergency bureau for victim identification; administrative work. Wiesje immediately volunteered and left with some colleagues for the Nijmegen Auction, where the remains of the victims were gathered. In the following days, she spent time collecting hastily written notes: “foot with brown vanHaren men’s shoe, size 42.” Or on another note: “Woman’s torso and arm with light blue blouse and silver wristwatch,” with a number indicating where the respective body part could be found. Wiesje then searched for the note with a similar foot, leg, or piece of clothing and put them together so that the body parts could be roughly matched. Fortunately, she didn’t have to do the final assembly herself. Survivors then came to identify a friend or family member based on the body or clothing or objects. Once this was done, the name was tied to a card attached to the corpse. Gruesome work, but Wiesje could shut down her emotions enough to perform her task efficiently without thinking about what a note concretely meant or that a body part had recently belonged to a living person. It took eight days to find all the bodies in the rubble, number the body parts, and put them together. After that, Wiesje’s task was done, and she returned to Dobbelman; where the atmosphere of before never returned. The cheerful girls’ club they had always formed had in one stroke become a group of serious adult colleagues.

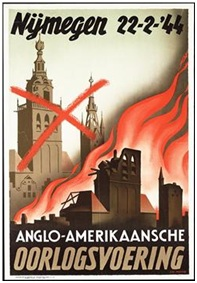

A few days after the bombing, the Germans were quick with their pamphlets: A drawing of Nijmegen on fire with the caption: “Anglo-American warfare.” The people of Nijmegen were shocked and in deep mourning, but they did not want to harbor hatred against the Americans. To the great frustration of the Germans. It became increasingly clear to the people of Nijmegen that the Germans had lost the war, and they made it known in their attitude. Especially the NSB members had a hard time. Their response was a primitive witch hunt against everything that could be resistance, red, or Jewish.