Westerbork

On the evening of Wednesday, March 8, 1944, the Rubens family sat at the dining table reading by the light of a single lamp when a soft knock came at the door. An unknown Nijmegen policeman stood outside, briefly inquiring if Theo was Mr. Rubens. He came to warn that a German raid would take place that night. “Make sure you’re gone,” was his advice. Toos covered her mouth with both hands, inhaling with a wheezing sound. Theo tried to calm her: “I’m fortunate to have been warned in time. I’ll go to Sjef immediately, but I think I can safely return in one or two days.” Sjef was Toos’s brother, also living in Nijmegen. Theo would be relatively safe there. Theo gathered some belongings, bid farewell to his wife and children, assured them he’d be back soon, and left. He had just turned the corner when he encountered another Dutch policeman: “So, Jew, out on the street after curfew without a star? That will cost you dearly.” It turned out to be a simple trap set by the two policemen, who pocketed the tip money they received from the Germans for every Jew they brought in. Rarely had the saying “one man’s death is another man’s bread” been so literally true. The policeman took Theo to the police station. Toos was informed by the neighbors, who had seen Theo being taken away, and she was at the station in less than fifteen minutes. “Your husband has already been transferred to the Germans in the barracks,” was the answer to her inquiries. “He is going to Westerbork in Drenthe. So, if you can bring a suitcase with some things for him. Not too much; just one suitcase. More cannot go.” The message, though not unfriendly, was harsh for Toos. She managed to hold back her tears but didn’t know how fast she had to leave the station; back home. Late that same evening, Toos brought a suitcase with some clothing and toiletries for Theo.

The next morning, she was early at the station. A German military truck stopped shortly afterward. Two SS officers jumped out, pulled aside the canvas, and opened the loading ramp. “Schnell, raus!” it sounded. One by one, seven men crawled out of the back, which was not easy because they all had a stick in their pants. “Schnell, schnell!” barked one of the SS officers. Theo was the last to come out of the truck. Toos ran towards the platform to say goodbye to Theo but was stopped by a stationmaster. “You are not allowed on the platform,” the man said sternly. Toos pleaded with him, but she had never been so strong in debates and convincing others. The stationmaster looked at her briefly and somewhat pityingly. “I really can’t let you on. This is not a passenger train but special transport, and I have no say in that.” Toos left the station and stood a little further along the fence next to the track. Theo had been brought to the station early that morning, along with six other Jews who had been arrested that night. Around nine o’clock, a train arrived at the station. A diesel engine from the Dutch Railways. The train was already full of people, mostly Jews, guarded by German soldiers. “Get in!” was shouted, and Theo grabbed his suitcase given by the police that morning and got in. There was no one else on the platform. He hadn’t been able to say goodbye to Toos, so he decided that he would write her a letter as soon as he arrived. The train had not yet gained speed when he saw Toos standing on the side. He opened the window, waved, and shouted her name loudly. She saw him, and crying and shouting, she ran along with the train for a few meters. Theo couldn’t hear amidst the noise of the train and the farewell cries, but he knew she was shouting, “I love you.” Unwillingly, he felt tears in his eyes.

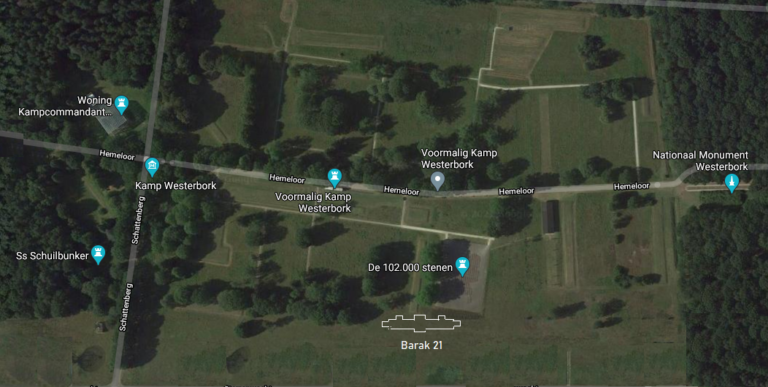

Most in the packed train looked very bad, thin with sunken faces and dirty, often repaired clothes. “We were in Camp Vught,” said a man whose age was no longer estimable. “Terrible; I hope Camp Westerbork is better, but it can’t really be much worse.” Theo couldn’t reply and stared ahead. The train stopped for a few minutes in front of Deventer station to wait for a train to Germany to pass. “Dutch SS,” said the policeman accompanying them, unsolicited. “They’re going to fight the Bolsheviks in the East. At least these are guys who have something for their fatherland!” Shut up, jerk, thought Theo, but he remained stoic, looking ahead without a trace of hatred. Shortly afterward, the train continued its journey; without stopping in Deventer, it continued past Zwolle, Meppel, and Hoogeveen. From the village of Beilen, they were driven further to Camp Westerbork with a horse and wagon. (See declaration)

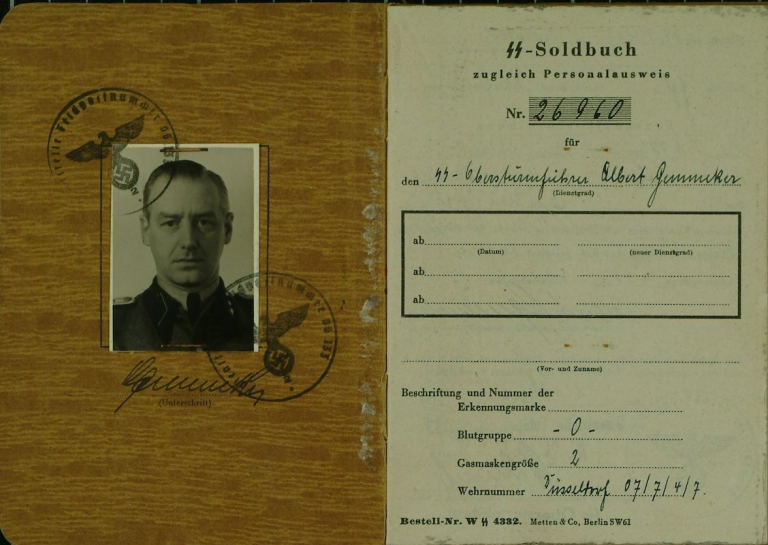

Theo was immediately placed in barrack 72, the punishment barrack, upon arrival. Five days later, on March 14, Theo was summoned to the camp commandant Gemmeker. “You should have stayed in the punishment barrack awaiting transport, but apparently, there has been a mistake,” Gemmeker said in reasonably good Dutch. “You’re married to a Dutch woman? Then, they shouldn’t have put you in the camp yet. You’re granted a few days of leave to say goodbye at home. Report back here by 2:00 PM on Monday, March 20. And make sure you’re here because otherwise, 14 Jews from here will be put on extra transport. And we will always find you.”

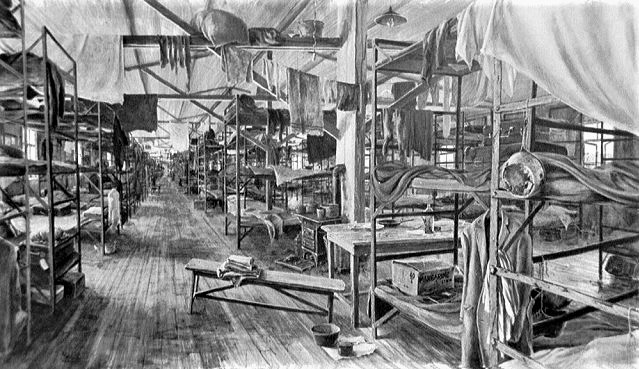

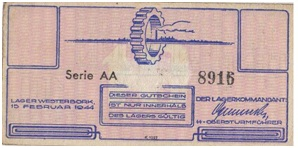

Gemmeker His return home was emotional but overshadowed by the knowledge that the lives of 14 people rested on his shoulders. Toos saw how Theo suffered and did not insist on him staying. The following Monday, Theo was already at the gate of Camp Westerbork by noon. A man from the Jewish Council approached Theo. “Thank you for coming back. Come with me, and we’ll register you. You’ll be assigned to a barrack. If you’re lucky, you’ll get a bed there. It’s not certain because it’s been overcrowded lately,” said the man from the Jewish Council – introducing himself as Ben – kindly. Theo followed him to a building. They entered a modestly furnished room. Behind the desk sat a man in a German uniform. “Name, age, address?” said the German in German. Theo provided his information, which was noted on a card. “Can you play music well? Or do you engage in cabaret or other theater, or are you a teacher?” “Name something you’re good at,” Ben whispered softly in his ear. “I’m healthy and a very good cook,” Theo immediately said. The German looked at him with a tilted head. “And now you want to showcase your skills in our top restaurant in this luxury resort? We have enough cooks. But you can help in the central kitchen. You’re in barrack 21, hall 2. There’s still a bed available there after this Tuesday’s transport.” And the man filled in behind Theo’s name: central kitchen. Barrack 21 was a large wooden shed with wooden bunk beds; three stacked on top of each other. It smelled of damp clothing and bedding, feverish sweat, mold, and who knows what else. It had started raining outside, and it was overcrowded inside, but no one greeted him. Ben searched for a while and eventually found an empty bed, the top one of the three, halfway down the barrack. Others quickly removed personal belongings from the bed and placed Theo’s suitcase at the back of the bed.

Barak 21 in 1967

“Come, let’s go straight to the central kitchen. Then you can see where you’ve been assigned to work. A good job! You’re lucky.” Ben led Theo around the camp, showing him the infirmary, the punishment barracks, the baby and toddler room, the sports field, the theater, and finally, the central kitchen. “This is Theo Rubens from Nijmegen,” Ben announced loudly to the prisoners working in the kitchen. “He’s assigned to your group; help him get started.” Back in the barrack, the man on the bottom bed approached him and introduced himself as Sam. “They call me Sammy. I understand you already have a job here in the central kitchen. You’re lucky. If you have a job, you’re not put on the list so quickly.” “What list?” Theo wanted to know. “The transport list. The people going to the labor camps in Germany or Poland. Most go to Poland. Concentration camps. They say that’s the journey into death. Every Tuesday, a train departs. A freight train. The evening before, names are called out. If your name is on it, you pack your belongings and, along with many others, are loaded into the wagons with a small barrel of water and a poop barrel. On the Boulevard des Misères, as we call the lane next to the tracks. And then, every Tuesday evening for those left behind, there’s the ‘Bunte Abend.’ I play in the camp orchestra. So, my name wasn’t on the list yet.” From that moment, Theo and Sammy spent a lot of time together. Every Tuesday evening, Theo sat in the Great Hall of the camp, where there was an exuberant attempt to forget that another train full of fellow campmates had ridden to their death.

For Theo, deportation to an extermination camp depended on two things: whether he could still perform useful work in Westerbork and whether, according to the rules, he was not yet eligible for deportation because he was married to a non-Jewish woman. He worked in the kitchen, so he was indeed useful. But was that enough? It seemed crucial to prove that he was married to a non-Jewish woman. And that was not so easy. He had to present a series of papers for that. The urgency is evident from what he wrote about it in the letters home:

March 22, 1944

Immediately have the papers of Mama’s lineage sent and order them from Not. van L. Nieuwe L. V. Bosch in Amsterdam. Everything depends on that because I need to have proof; otherwise, there’s a chance of being forwarded. Martin Posno and his wife are only here briefly, but I don’t think for long. I’ve been assigned work, which I find good; it helps to forget a lot.

April 24, 1944

Dear wife and children. To my great regret, I still have no response to my last letter and no package for which I sent a stamp. You understand that I find such a thing very distressing. But I hope I’ll still receive it. Now, pay close attention. I still need a baptismal certificate from your grandmother Anna Maria v.d. Graft, born on March 25, 1833, in Alem. As you know, the municipality of Alem forgot to mention the church denomination. Maybe Wim has such a document; otherwise, someone must urgently go to Alem because I’m temporarily barred only until May 1, so that must be sorted out. Furthermore, send this to the address where the other documents were sent, along with my identity card. So, once again, proof that your grandparents Decates were Catholic.

Daughter Beppie responds:

April 26, 1944

Trust that everything will turn out for the best. We’ll bring everything you need to the J.R., who can ensure faster delivery. In any case, with or without J.R., you must have everything before May 1. There can’t be any question of mixed marriages being forwarded; that curfew will probably be extended. Be strong, trust in God, Beppie.

April 12, 1944

It’s really tough here with Arts and Science. Many acquaintances work with me, including Johnny and Jones. Martin Posno and his wife have left. Besides them, there’s no family here. Blackout well because everything is charged against me.

Music, art, it continues to sustain the camp residents. No one outside the camp can imagine how precisely this helped the prisoners endure the inhuman madness of awaiting destruction. The Germans understood that this made the prisoners feel somewhat human for the time they were still allowed to live. Music made life in the camp seem bearable, or at least, it allowed them to momentarily forget that the death of destruction was anxiously close. The well-known duo Johnny and Jones were in the camp. They didn’t play in the camp orchestra because they didn’t sing in German, but they performed in the camp coffeehouse. They did not survive, despite their contribution to the cultural life in Westerbork. On September 4, they would be transported to an extermination camp with the second-to-last transport. Theo writes about them to his family but also casually mentions that his relatives Martin Posno and his wife have been transported (“sent by”) to an extermination camp.

Wednesday.

The day before, as usual, a transport had departed eastward. But today was not like the others. The entire camp was thoroughly taken care of. All barracks were cleaned, flower boxes were placed at the platform, two large ferns were set up in the large hall, and the kitchen received various types of meats, cheese, and butter to prepare an excellent lunch. Because the Red Cross was visiting. Instructions were given: “…if you’re asked something, answer briefly, look friendly, and show how well everything is organized in our camp.” At half-past eleven, three cars entered the camp with the Red Cross flag. Theo had been busy in the kitchen for a while preparing lunch. A selected group of camp residents was asked to join for a lunch like they had never had in Westerbork. It created an appearance of bliss on their faces, which could easily be interpreted by the Red Cross companions as contentment with their fate. An hour after lunch, after a brief inspection of the barracks, the group entered the kitchen, engaged in conversation with their German escorts. When they reached Theo, a somewhat affectedly speaking lady remarked, “It must be quite a challenge to prepare food for so many people. It surely helps that the kitchen is well-equipped?” And she continued without waiting for an answer. After lunch, the group left again after shaking hands with Gemmeker and the German escorts. “Well. We won’t see them again this year,” remarked kitchen mate Bram. “Gemmeker has passed his exam again, and as for us, those bastards at the Red Cross are not interested.” Theo nodded in agreement. “Humanity. It’s not meant for us.”

June 12, 1944

We have the Pentecost days off from work. The first day, I spent as follows: from 12 to 1, bathing, eating, 1 hour lecture by Prof. Cohen and Dresden. In the afternoon, I cooked for the group, potatoes, green beans, pudding, then a concert by Sam Zwaap on the violin, Leijdendorff on the viola, Canter on the cello, Korenstein on the piano. Today, the same. Furthermore, we have a revue with comedians Frans Engel, Paul Erich, Otto Aurlch with his wife, Ester Philips, Jetty Canter, etc. The best we can get.

But every Tuesday, he could be found at the train. In the central kitchen, he secretly took food, hiding it in the empty poop barrel for those going on transport. He made sure to stand next to the cart with barrels of water and poop barrels when loaded into the train by the prisoners of the Fliegende Kommando. To those who waited patiently for their last journey into the train, he would softly say, “There’s water in the barrel for the journey. And also some food.” And although more and more people in the camp knew about the illegal food supply, it was never talked about. Theo was treated with great respect because everyone knew that they could be the ones designated for the food that Theo had stolen for them the next Tuesday.

Theo Rubens (with hat) by his cart with barrels.

See Theo Rubens in “Jew hunters”

In early September, Theo wrote in a letter home: “I will be leaving here for an exchange camp in Germany soon. Maybe I will be exchanged through Switzerland and hope to be with my wife and children. I love you all and look forward to reuniting with you. Kiss the children for me.” The following Tuesday, on September 13, 1944, the last train departed from Westerbork to Bergen Belsen with 279 people, but without Theo, who was not on the list. Not many people were left in Westerbork—just over 500 Jews and about 300 arrested people in hiding. It became a strange time of uncertainty and waiting, and you could sense that the Germans were trying to present themselves in the best possible light. Camp commandant Gemmeker walked through the camp regularly, sometimes greeting people kindly. Theo’s friend Sammy continued to play in the camp orchestra, where the famous violinist Bennie Behr, released from the punishment barracks, also played. It took a long time before there were cautious whispers that there would be no more transports from Westerbork.

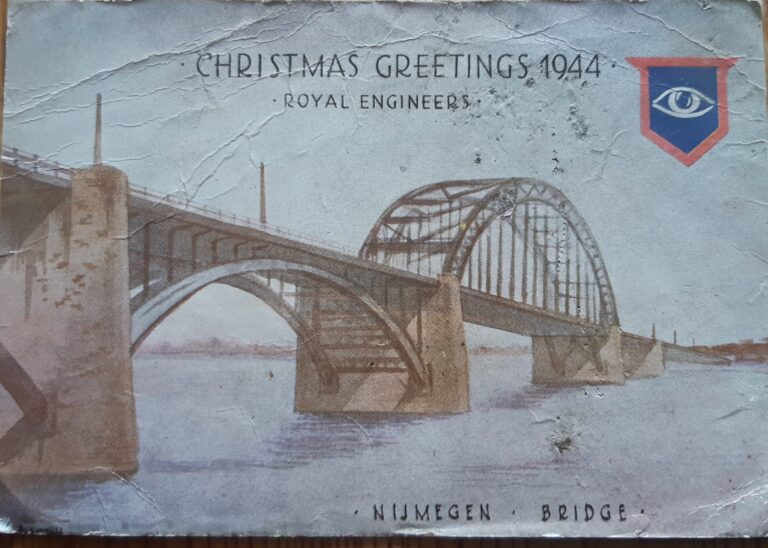

Nijmegen has been liberated. The Rubens family has returned to Mariënboom, now confiscated by the British and Canadians. The company at Mariënboom, led by Beppie and Wiesje, provides pleasant relaxation for the soldiers returning from the battles at the Waal. However, the prisoners in Westerbork cannot go home yet. Part of the Netherlands is still occupied by the Germans, including Westerbork. On her birthday and that of her father Theo, February 19, 1945, Wiesje writes:

February 19, 1945

Dear Papa, Today, we are celebrating our birthdays, and you can certainly imagine how much we miss you. We wonder where you might be at this moment and under what circumstances your birthday is passing. It will not be easy, in any case. You understand that today is not a festive day for me either. Will we all be together again for our next birthday? It seems that the war is ending now, and we’ll just have to hope for the best. So much has changed since you left here. My engagement with Jo has been broken off. I know how you must feel about me now, and if you knew everything about me, you would truly be angry with me. But now that I’m entering a new year (I’m turning 23, old, isn’t it?), I have decided to improve my life and not do any more foolish things. We will tell you everything when you are back here, and we pray together that this won’t take too long. Don’t worry too much and try to get through it as we are accustomed to from you. A warm embrace from Wiesje. Now, Papa, I’ll end again. Hopefully, we’ll see each other again soon. I believe that it will be something so tremendous. We’ll be overly happy in the first weeks. Much love, Wiesje.

On April 11, a rumor spread that the Canadians had broken through in Drenthe. Gemmeker sent a small train with goods from the camp and left with other SS officers to Leeuwarden. Despite a notice stating that Westerbork was now under the protection of the International Red Cross and warning that leaving the camp was life-threatening, several prisoners hastily left. Aad van As, a Dutch civilian who did not live in the camp, had been in charge of distribution in Westerbork from the beginning. The supply of the central kitchen also fell under his responsibility, and Theo knew him as someone who tried to make the suffering of the camp residents somewhat bearable. The prisoners had earlier asked Aad to take charge if the SS were to leave. Under his leadership, most of them now awaited the liberators. Theo also stayed to help with food for the remaining camp residents. On April 12, the cry went through the camp: “the Tommy’s are here,” and everyone rushed to the camp farmhouse to cheer the liberators. Captain Morris, the commander of the Canadian troops, was greeted by a cheering crowd singing the national anthem, but he had an unpleasant announcement: not all of the Netherlands was liberated yet, and for their own safety, everyone had to stay in the camp until further notice. Not everyone complied; some left as quickly as they could. The camp came under Military Authority, and from April 24, 1945, arrested NSB members and Landwacht members were imprisoned there. The original camp residents were tasked with guarding these new prisoners, and no one was allowed to leave the camp without the permission of Military Authority.

Theo wanted to leave the camp immediately after the arrival of the NSB members. He refused to become a guard for that group, and besides, it was a shame that they still weren’t allowed to leave. He spoke with Henk, the driver of the food supply, who turned out to be from Nijmegen. He drove for the Canadians and now also drove the truck bringing food crates to the camp. Theo suggested that, against the rules of military authority, he would ride back to Nijmegen with Henk. In the afternoon, Theo hid among the empty crates that had held supplies for the camp, and they easily passed the guard post at the exit. Back in Nijmegen, he first had a strong drink at Henk’s home before going to his own family. But he had no rest in the following days. Two fellow prisoners from Nijmegen were still in Westerbork. He agreed with Henk that the truck from the food supply would also pick up the other two Nijmegen residents. On May 1, 1945, he wrote to them:

Nijmegen, May 1, 1945

To the Nijmegen residents. Dear Friends. The bearer of this letter will come to pick you up now. Pack your things as quickly as possible, go through the garage, and don’t wait any longer; the rest will be taken care of. I also had a prosperous journey and am very glad I did not hesitate. I have consulted with your wives, and they expect you to do as I have done. So, until we meet again. Your devoted I.B. Rubens. You will first go to Winterswijk and then to Nijmegen; lodging and food will be arranged.

Hotel Mariënboom was in ruins. The Germans, who had thought of staying in Mariënboom for a long time, had been polite and had maintained the hotel well. In September 1944, English soldiers were quartered in Mariënboom, who had to fight daily at the Waal.

In December, a large part of the English forces departed towards Belgium, where Hitler had initiated the Ardennes Offensive.

The English soldiers were relieved by Canadian military personnel who were considerably rougher than the English. Both the English and Canadians were frontline soldiers. Mariënboom served as their resting place after a long day of fighting, where they tried to relax and release the frustrations of war. They slept on the first and second floors. The boys on the first floor decided not to carry their waste downstairs and had drilled holes in the floor through which they discarded their refuse. The basement, the banquet hall, had been used as a garage for military vehicles, as well as the garden. The furniture had frequently been used in their internal fights, with table and chair legs broken off to be used as weapons. The kitchen was completely ransacked and destroyed. The tennis courts were used for military vehicles. The swimming pool was ruined. The animal pens in the backyard were destroyed, and the animals were dead. Moreover, valuable items from the hotel were looted by neighbors in the short period between the Germans’ departure and the Rubens family’s return. The neighbors even had to be forced to leave Mariënboom by Barend, the son who had joined the domestic forces, under the threat of a gun. They didn’t see why the Rubens family should get the hotel back; after all, they had left.

Theo was not received with a grand celebration. The family had trusted all along that he would return, but rumors that all Jews had been murdered created growing doubt. The joy and gratitude were profound, and tears were shed for days. However, the circumstances were not festive, and Theo himself was silent, closed, and looked unwell. There was no help to continue living. Still, it was clear that Mariënboom had to be completely rebuilt. Theo tried, against his principles, to borrow a small amount of money from the municipality to repair the most significant damage and reopen the hotel, at least the café and the restaurant with a terrace. Only in 1948 did a small loan come through, and the hotel could reopen. The beautiful garden with tennis courts and a swimming pool was never restored. There were not many income sources because the entire Netherlands was in a phase of licking wounds and reconstruction. People were not yet ready for entertainment or holidays. A welcome source of income from 1950 onwards was the repatriates from the Dutch East Indies who were accommodated all over the Netherlands. In Mariënboom, the entire first and second floors were claimed for these repatriates by the government.

Since the hotel was closed in the first years after the war, another way had to be found to earn money for the Rubens family’s livelihood. Wiesje and Beppie went to Amsterdam, where they found jobs at the Eva Produca vacuum cleaner factory. They lived together in a small room near the Amstel. Most of their earnings went directly home, but that didn’t stop them from enjoying life in Amsterdam and their newly acquired freedom. It was late spring 1946, a beautiful sunny day. Wiesje and Beppie decided to rent a rowboat and row on the Amstel. It turned out to be less relaxing than they thought. Wiesje’s motor skills were not great, and for the first five minutes, they barely moved away from the shore; they kept circling because Wiesje exerted twice as much force with her right paddle as with her left. Eventually, Beppie took control. She was a bit stronger and more resolute, rowing the boat alone and in a reasonably straight line from that moment. Wiesje sat like a princess on the back seat, enjoying the sun and the surroundings. She was the first to see that a rowboat with two young men was making a successful attempt to overtake them. The men were certainly not unattractive, and one looked a bit like Wiesje’s deceased friend Louis. Almost routinely, Wiesje smiled at the men who had come about five meters alongside them. The men smiled back and steered their boat alongside. “Hello, ladies,” Leo began, “also enjoying the lovely weather and the water? Do you live in Amsterdam?” “Yes,” Beppie replied, “not far from here. We work in Amsterdam, but we come from Nijmegen.” “We’re not from here either, but we’re also here for our work. We work at the Amsterdam branch of Ruys; and you?” “At Eva Produca,” Beppie replied. “Well, my name is Leo, and this is my friend Joop.” “Hello, Joop, I’m Beppie, and this is my sister Wiesje.”

When Joop and Leo noticed the boat with the two girls, Leo immediately said, “We’re going to board them, Joop.” Joop laughed. They rowed harder, and quite effortlessly, they overtook the girls’ boat. “See that one with the long blonde hair, Joop? Looks like a nice one.” “I noticed that too. But this time I get the first choice, Leo. She’s reserved for me. The other one doesn’t look bad either.” Leo made a broad grimace. “Don’t do that to me too often, Joop. But okay, try to charm her. If it doesn’t work, we can always trade.” Leo pulled the boat of Beppie and Wiesje against theirs and tied the two together. It clicked almost immediately between the cheeky Beppie and the just as cheeky Leo. Joop and Wiesje each sat in their own boat at the back and looked at each other. “Usually, I can’t get a word in when my sister starts talking.” said Wiesje. Joop laughed. “Well, if Leo is loose, I don’t need to open my mouth either.” With a look of connection, they continued to look at each other for a while and then engaged in an animated conversation about the weather, the Amstel, and rooms in Amsterdam. Wiesje told Joop that the landlord regularly dropped by and made nasty remarks. “That’s not right.” Joop said. “Shall I talk to him?” “As long as it doesn’t turn into a fight, because we don’t have another room right away.” Later, when they had said goodbye and exchanged addresses, Joop said to Leo, “I agreed with Wiesje that I’ll visit her next week. Supposedly, I have to solve a little problem with their landlord.” “Well done, Joop, that was fast,” laughed Leo. “Should I come with you? Then I’ll keep myself busy with Beppie while you converse with their landlord.” A week later, Leo and Joop stood on Beppie and Wiesje’s doorstep. They had both bought a bunch of flowers. Beppie let them in, but when they came upstairs, Wiesje didn’t seem very happy. She sat grumpily looking ahead. “Sorry,” she said, “I’m incredibly angry, but you can’t help it. The landlord has been in our room when we weren’t there, and now all our money is gone, 400 guilders. We immediately went to the police, but they laughed at us and said: yes, that’s what happens when provincials want to live in the big city. Truly scandalous. What should we do now? That was money for our parents.” “You shouldn’t stay here any longer.” Joop said resolutely. “I’ll help you find a new room right away.” In the following days, he walked all over Amsterdam looking for an affordable room for the two girls. But there were many more housing seekers than there was living space, and with shame, he had to tell Wiesje that it hadn’t worked. “It’s okay, Joop. We’ve already decided that we don’t want to stay in Amsterdam. We’re going back to Nijmegen and will find work there.” And Wiesje spontaneously gave Joop a kiss on the mouth. “Can I write to you?” Joop asked. “Of course! I would be terribly offended if you didn’t.”

On May 28, 1948, Joop and Wiesje got married in Nijmegen.